Akkara Coyette - Community Kitchen

I lost my job in April due to “economic reasons.” It’s the first time I’ve ever lost a job. If you’ve ever been laid off, then you know it can be devastating–especially when it’s unexpected. With it comes a rash of emotions from fear, uncertainty, and a disconnectedness, along with an aimless, depressive, purposelessness. All relatively in the same ballpark, I guess. I wallowed, often in bewilderment, wondering what on earth I was going to do.

I made a list of things to accomplish named “funemployment,” a term my wife liked to throw around. I was going to read more. Write more. Make a Sri Lankan curry powder. I was going to join a gym, swim, and run more. I made a large batch of preserved lemons. I made my own orgeat syrup. And I did my taxes. I also downloaded the Serve the City app.

As someone who loves cooking, craves dinner parties, and has to actively be stopped from hoarding spices, volunteering in the Community Kitchen sounded like a nice way to pass my time. It was my wife who had originally recommended volunteering, who, in between jobs back in 2023, volunteered herself, in the same kitchen. She spoke nothing but positive of the experience, citing the chill nature of the staff, “the feminine energy,” as she put it, and the laid-backness of it all.

For my first shift, as required, I signed up for one of the vacant “portioning” slots. I, along with a few others, scooped portions of a vegetable based sauce, rolled out from the kitchen in large pots, mixed with rice, into small aluminum takeaway containers, which are then covered with a cardboard lid, and sealed by folding the corners inward. It took us a little over an hour to fill the required number of meals for the day.

On my second portioning shift, a little braver, I asked about joining the volunteers in the kitchen.

- - -

At only 26, Akkara Coyette is already a chef de cuisine. For most her age, working in a kitchen or restaurant, such a position would still be many years off. As chef de cuisine, Akkara not only cooks, but runs and manages the kitchen and two sous chefs. She handles orders, inventory, and in the case of the Community Kitchen, donations. “I’m like a child boss,” she jokes about her age and responsibilities.

You can find the Community Kitchen located in the basement of the Holy Trinity Brussels Anglican Church on Rue Capitaine Crespel just a block off Stephanie. Unlike most churches that announce their presence with towering spires and bell towers or ornate facades, the Holy Trinity Brussels Anglican Church rather sits back from the street, behind which could easily be passed over as just another Brussels house, with only the words HOLY TRINITY and a small white cross bolted above one of the windows. It is here, everyday, that the small kitchen makes meals for those in need.

Often Akkara works all day. She is joined by two sous chefs, Anjali and Roya, who, when Akkara is handling the management side of the kitchen, take over most of the cooking duties. There’s also the operations manager, Aline, who handles the organization of the volunteers and the day to day. These four, along with an ebb and flow of volunteers, produce on average, 1000 meals a day.

As of today, the Community Kitchen supplies meals for two main locations–Hub Humanitaire (known around the kitchen as simply “the Hub”–and the Red Cross Center on Rue Belliard. The Hub, a day center located on Avenue du Port, adjacent to Tour and Taxis, is the Kitchen’s largest recipient of meals, with hundreds of meals, lunch and dinner, provided each day. At The Hub, those in need are able to have a hot meal, take a shower, and receive basic medical attention. Though due to it being a day center only, those in need must find other accommodation for the night.

Entering through the iron gate one gets their first glimpse of the church’s stained glass windows. A small sign that reads, “Church of England, Christ Church,” directs the congregation inside. Entering the church I immediately feel like a fish out of water. I can’t remember the last time I’ve set foot in a church for more than a couple minutes to admire the architecture, let alone to be active in any way.

Heading down the stairs, directed by the signs leading volunteers to the community kitchen, I enter a hall full of tables and drying aprons and dish towels. Aline, one of the Kitchen’s full time employees, welcomes me, as she checks who has registered to volunteer for the day and begins preparing for the portioners arrival. I hang my backpack on the coat rack, wash my hands, put on an apron and hairnet and bring myself to the kitchen. It’s 9am.

Often I am the only volunteer in the kitchen, and if not, I’m typically the first volunteer to arrive. Akkara already has the music on, often playing Doja Cat. Anjali, another of the kitchen’s employees, is in the back room eyeing the coolers and what ingredients we have to work with today. It’s Wednesday, so that means it’s orzo.

We fill three large tubs with orzo, 500g at a time. Once we’re finished we fill the tubs with cool water so the orzo can soak.

“Onions?” Akkara asks.

I return the coolers and the pantry and grab a 10kg bag of onions from the shelf. Throwing it over my shoulder I haul it into the kitchen where I begin my prep. I lay down a cutting board, and grab the sharpest knife I can find–which can often take two or three attempts to find one I’m confident with. I slice off the tops of each onion, making sure to keep the roots intact so as to reduce the concentration of eye watering chemicals. After cutting the onion in half, I remove the outer layer from both halves before slicing three horizontal cuts into the vegetable. Then, moving to the top, I made half a dozen vertical cuts from top to bottom, before positioning my knife perpendicularly, dicing the onion into a small pile.

One down, 45 to go.

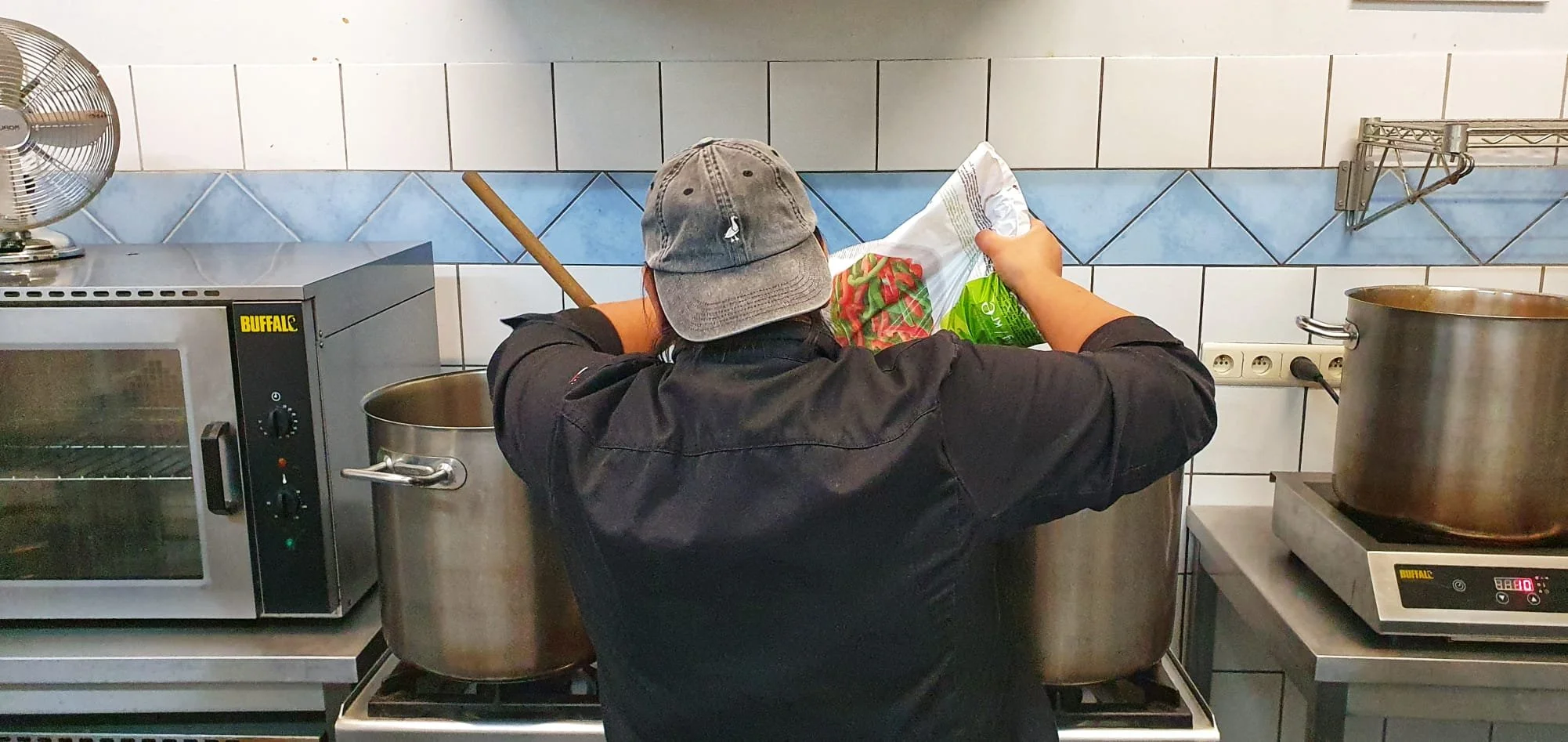

When I finish with onions, it’s on to cauliflower. The frozen bags of cauliflower, having been defrosted in cool water, are strained and quartered. I assist with stirring the large pots, of which now are nicely browning the onions I’ve diced previously. Bell peppers are added, along with tomato sauce, and seasoned generously with herbs and spices. After that has reduced, the cauliflower is added and the sauce cooks down even further.

The orzo, now hydrated, is drained and added to the pots of sauce. Anjali offers me a spoon to taste. A little salt is added, and left to simmer.

By now it’s a little after 10:30 and the crew of portioners have begun to arrive. Clad in hairnets and aprons as well, they make talk amongst one another in anticipation of the first pot.

Once cooked down, the large pot is loaded onto a trolley–often by two people–and wheeled out into the hall where it is portioned, boxed up, loaded into vans, and delivered across the city to the HUB where it will still be hot when it arrives.

One by one the pots return to the kitchen. The dishwasher is currently broken, so everything must be washed by hand. Using steel wool, I scrape away the baked bits at the bottom of the pot, rinsing it with the powerful and hot spray nozzle before scraping again. Anjali insists I don’t have to do it, but it has to be done so I do it. Each pot, dish, spoon, and staff coffee cup is washed, dried and put away. At this point, most of the portioners have left.

Akkara and Aline are in the hall working out the numbers and preparing for their next order.

“There’s some extra grapes in the cooler, if you want them,” Akkara offers for my day’s work.

I wash up, discard my hairnet, and take my backpack from the coat rack. My entire front is wet from the splashing water of the dishes. My back is a bit stiff from being on my feet all morning. My hands, pruney and shriveled from the water, smell like onions.

“See you next week,” I say with a nod, putting a tub of grapes into my backpack.

- - -

It’s important to do away with a few stigmas and misrepresentations that often come with cooking in a place like the Community Kitchen.

First, the meals are all prepared by professionals. Akkara knows her stuff. Having trained in cooking in Namur for six years, Akkara is a highly certified chef with the qualifications to back it up. Having been given the option of restaurant cooking or more industrial focused food preparation, Akkara chose the industrial side for one simple reason–the hours. As a chef in a restaurant, one often has to work crazy hours as well as weekends. Akkara wanted to cook without sacrificing time for her family and friends. In her training, Akkara not only learned front of house and the kitchen, she trained as a server, while at the same time learning advanced plating techniques and cooking methods. In her last year of training she learned the nitty gritty of what it means to be a chef de cuisine–ordering, managing money, and telling people what to do.

After completing her studies she worked as an intérimaire, or temp worker, for a few months, but often found the colleagues hard to stomach. “They were all real alpha men-type. Gross and mean,” she says of those early working days. “I knew I wanted to leave that.”

During this time she briefly thought about changing, studied caretaking for one year, but a stage during COVID traumatized her, redirecting her back to cooking. Akkara started volunteering in the kitchen while she also was looking for a job. For a year she found herself depressed. “I would tell people I was fine,” she says, reflecting on that time, “but clearly I wasn’t.”

Her first day as a volunteer was on a Sunday making muffins. “It was really fun,” she remembers, “I came back day after day.” Not long after, the boss offered her a leadership position, which eventually evolved into a paid position, as the project grew bigger and bigger, making Akkara the first paid employee of the Community Kitchen.

Before Akkara came on full time in 2021, most of the ordering was done by eye-balling what was in the coolers at the time. Bringing with her her training and know-how, Akkara helped to streamline the kitchen into a well oiled operation. The project continues to grow, in part due to more and more organizations reaching out to the community kitchen for their services, but also because things are generally getting worse and worse for people.

With help from Serve the City, a volunteer organization in Brussels, the Community Kitchen began recruiting the help of daily volunteers. Serve the City’s ServeNow app is very helpful, as it allows volunteers to easily sign up for shifts, while allowing the managers to remind volunteers, send messages, and coordinate efforts. Despite this, it can still be difficult to find volunteers–especially during the summer and the holiday times.

Reliant on volunteers for much of the daily work, Akkara says some of the volunteers who come in for the first time, are scared of being in the kitchen. “Social media projects, this like, classic mean, yelling chefs.” Akkara assures me, “If you can boil an egg, there’s room for you here. The Community Kitchen is a place where we welcome everyone.” Race? Religion? It doesn’t matter. Often the kitchen and portioning hall is full of volunteers from all over the world, with some volunteers having been doing so since as far back as 2019.

It is also important to understand that all of the meals prepared in the Community Kitchen are prepared without any federal funding, but instead entirely by private donations. Even the pots and pans are via donations. It’s only when something is desperately needed, the Community Kitchen must resort to buying it. After a full renovation of the kitchen a couple years ago, with the help of a large donation, they bought new equipment, new tables, and carts. But every purchase is a negotiation, and they often must make due with what they have.

“We now have four ovens that work-ish,” Akkara says. She tells me about the kitchen’s previous ovens, and the sad state they were in at the time of renovation. As much as they would like to have better ovens still, and sharp knives, and even a bigger kitchen space, there’s often little that can be done without additional funding.

“It’s difficult, but we manage,” she says in somewhat of a defeated but accepting tone. “It would be nice to have better ovens, definitely.”

Despite the work she does, and the limitations put on her and the other chefs at the Community Kitchen, Akkara says some would equate what they make to “slop.”

“It is still food,” she says defiantly, and yes, the quality is different, which is to be expected being that they are unable to buy the highest quality ingredients, but they are buying fresh vegetables. For one of their portioned meals, the cost of preparation is only around 25 cents including paying employees, drivers, and everything else.

I ask Akkara if she plans on sticking around at the Community Kitchen long term. “We need funds, we need money,” she says in response. Even the employees are unsure if there will be enough funds to renew their contracts, and while Akkara has been the chef de cuisine here for two years, everytime her contract comes around for renewal, she hopes she’ll be able to stay on for another year.

This is a place where Akkara used to come to church. As a child, her mother wanted to go to a church that reminded her of England, and spoke English. Akkara and her sister went to Sunday school here. Her boss was her Sunday school teacher when she was 8 years old.

For many chefs, a kitchen is a second home. A ritualistic place that becomes not a second or third space, but the space. If you’ve ever worked in a kitchen you know how hard it can be to keep a chef away even on a day off. The connections made with the stainless steel work tables, the knives and wooden mixing spoons, the sous chefs, the ingredients, and the food ultimately produced, are for some what keeps them getting up every morning.

When I was in high school I worked at an old hotel that doubled as a restaurant. The staff, primarily made up of my fellow classmates, was responsible at various times of the year for the entirety of the hotel. At times, it was only a handful of 17-year-olds who were cleaning rooms, checking in guests, serving patrons in the restaurant, and even doing the cooking. Often the only one on staff of age was the bartender.

Popular culture has warped the minds of the public as to a typical chef’s demeanor. It’s hard to watch The Bear or Hell’s Kitchen, and not see chefs portrayed as some eccentric, over-the-top, borderline abusive personality that can range from Gordon Ramsay calling someone a donkey and an “idiot sandwich,” to Joel McHale’s character in The Bear who savagely berates and belittles his chefs in the smallest, quietest voice imaginable as the kitchen soldiers along behind him in total silence.

YES, CHEF!

This is hyperbole.

Our chefs often came and went. For some, they came with grand aspirations of running their own restaurants, planning their own menus, and dictating how and what was to be done. For others, discounts at the bar and free lodging were more appealing. Working in the immediate proximity to the kitchen, I tried many of my first “elevated” dishes, if you will. Made a few times by the chef, taught to the line cook, and replicated over and over again during lunch and dinner services. Filet mignon, monte cristo sandwiches, chicken corn chowders, and my personal favorite, the apricot glazed baby back ribs.

This was my first real job, and I learned a lot about myself. I, manning the front desk, welcomed guests, checked them in and out, arranged housekeeping, and, during restaurant hours, doubled as the host and the cashier. As a teenager, I didn’t have much say over when I worked. On schooldays, I started immediately after the bell rang, and on non-school days I could go from closing one night, to opening the next.

At the busiest of times, the entire kitchen staff included a line cook and the chef, as well as a dishwasher. When the restaurant closed, the chef dipped, and left us, my friends and I to make sure the dining room and kitchen were ready for the next day. It was then when we took to the grill, making our own hamburgers, sandwiches, fries, poppers, or whatever we could find in the prep kitchen. We ate our share of cheesecake and feasted on Andes dinner mints.

We survived dinner rushes, no shows, and staff shortages. We 86’ed dishes, and customers. Drank the wine leftover in the bottles on the tables, and shared champagne with the dishwashers. We sang “Happy Birthday,” for tips, gave our friends extra fries, stayed late when required and closed early when we could.

It was there, in the kitchen with my friends, that I fell in love with food and kitchens.

- - -

Akkara, along with her sister, was adopted from Cambodia when she was just three-months old. Her parents worked 15 years in Battambang, Cambodia in social outreach and health–her father, Belgian, a doctor for Médecins Sans Frontières, and her mother, British, a nurse and midwife. Her mother taught her how to cook and bake, which she didn't enjoy as much due to the precision needed, and her father has recently found his way into the kitchen as well. At home, she tells me they have a game where they rate one another’s dishes, “they’re always scared that when I’m coming around…”

She knew she wanted to cook at the age of 12. “We were all thinking I wasn’t made for university and normal studies,” Akkara tells me about her early days in school. She often didn’t get along with the teachers, and thought a life behind a desk doing office work would kill her.

I ask her if she’s ever visited The Hub, the day center where the food she makes in the Community Kitchen gets eaten. She tells me she has, and that while seeing the people eat and enjoy the meals makes her happy, at the same time she knows that those who eat there must eventually leave, which makes her sad.

“At the end of the day they’re all just outside. They don’t have a home, they don’t have much money, they have literally nothing. I feel happy, but not…” she tails off, thinking about her words. “I’m really happy to make them happy.”

- - -

A few weeks after I learned I had been laid off, I ran into a former acquaintance in the street.

As my wife and I rounded the corner from Rue de l’Aqueduc to Rue Africaine across from Church of the Holy Trinity in Bailli, I noticed a woman with a walker looking around in a disoriented fashion. Almost immediately I recognized her as being from one of my first pre-COVID French classes.

Crossing the street I called her name and was welcomed with a smile and she recognized me. We exchanged bonjours, and small talk pleasantries, as it had been nearly five years since we’d last seen one another.

Throughout our A level classes, we had often chatted at pause, gotten to know one another, and became, for three or four months, a fixture in each other’s lives. She was an active woman always discovering the city, who enjoyed luxury shopping and luxury brands, showing the class pictures she’d taken on her phone, and who always took the time to greet the entire class—“Bonjour tout le monde!” she would loudly announce—even when she entered the classroom twenty minutes late.

The walker she used to get around was new. She explained she had been plagued with a handful of strokes a year or so back, paralyzing her for a time, and confining her to a bed. She still hadn’t fully recovered and needed the help of the walker to get around. At times I could tell she still had problems speaking, and seeing her in such a way, the talkative, peppy person I once knew, was quite difficult.

After helping her orient herself and find the shop she was looking for, we parted ways. As my wife and I walked toward Louise, I couldn’t help but think about what I had. I may not have had a job, but I had my health, I had my mind, and I had my voice.

“Things could be much worse,” my wife said, breaking the silence.

“Much worse,” I affirmed.

- - -

“I really love food. It’s really a passion,” Akkara tells me with a smile.

I ask her if she’d ever consider opening her own place. She tells me she’s always wanted to open a bistro/bar place, but leaning more towards bars now. She mentions in the same breath all the difficulties one can face opening a restaurant–the high failure rate, growing a customer base, the cost of everything. “Something where everyone is welcome,” she includes. “You can even bring a dog if you want!”

I follow up by asking her where she likes to eat in Brussels, if there’s anywhere in town that embodies what she would like to open. She hesitates for a moment. She tells me she likes the diversity of Brussels, but when it comes to eating out, Akkara says she often seeks out places where there’s not many people–something that seems quite contradictory to today’s Instagram-fueled-hypebeast restaurant culture. She acknowledges sometimes the food can be subpar, but other times it can be quite good. (Which, if we’re being honest here, is no different of an experience than one can get at any Insta-recommended-influencer spot.) Authenticity is what she seeks out over anything else—she’ll take taste over aesthetic anyday.

This is Akkara—Authenticity over everything else.

Now more than ever the Community Kitchen could use your help in the form of donations. By visiting https://communitykitchen.be/donate/, you can help keep the Community Kitchen going, and help the chefs and volunteers continue to provide meals throughout Brussels. A monthly donations of just 10€ provides enough ingredients for 30 meals. Your donations go a long way in making sure this vital resource continues into 2025 and the future. Please, if you can, donate.